The Table for the Absent

On October 3rd, I flew to Korea to document jesa, the Korean ancestral rite, during Chuseok. Jesa is a Korean ancestral ritual where families honor their ancestors through offerings of food and drink. I was there for only four days, yet what I witnessed—through food, labor, and ritual—revealed more than I expected about belonging, memory, and the quiet weight of tradition.

I was born in South Korea and immigrated to the United States at thirteen, a move that fractured my sense of home. As a child, I watched my mother and grandmother prepare endless dishes before dawn at my grandparents’ house. I thought we were expecting guests, but no one ever came. When I finally asked why, my mother said, “It’s for your great-grandfather and great-grandmother.” Only then did I understand that the table was set for the dead.

After I moved abroad alone, jesa faded from my daily life, but not from my family’s. Each time I returned to Korea, I would find certain dates quietly marked on the calendar: jesa. This project follows that ritual—from grocery shopping to the final bow—through the lens of both observer and daughter, searching for what was lost and what remains.

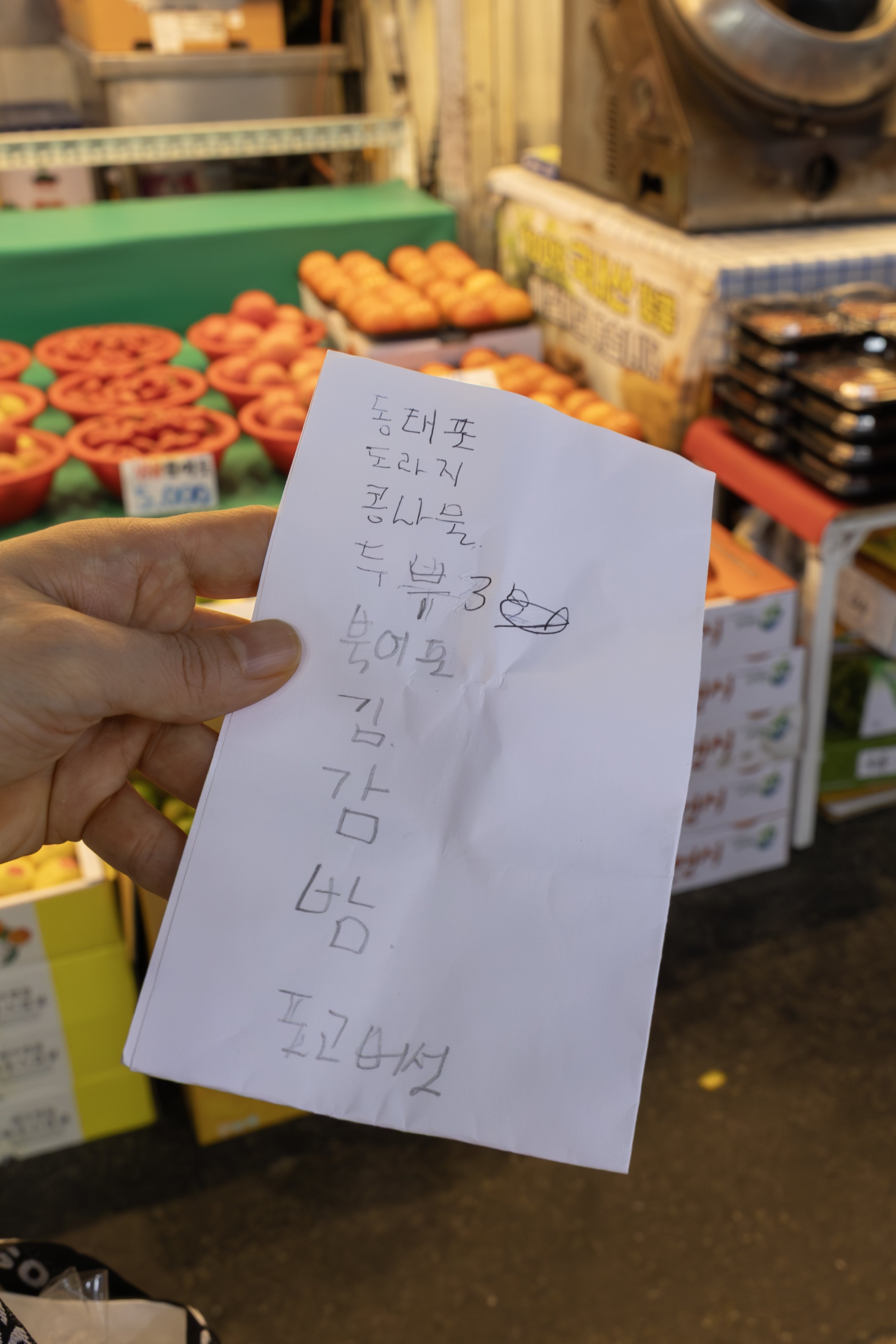

Grocery list: pollock fillet, bellflower root, soybean sprouts, tofu (3 blocks), dried pollock, seaweed, persimmon, chestnut, shiitake mushroom

Always the taste tester — never the chef.

My mom's favorite

The day of Jesa starts early.

All for the deads

My aunts are getting ready, preparing to look presentable for those we are serving.

Grandpa walks in to check whether my mom and aunts are preparing the food the right way.

Dad stands behind Mom, peering over her shoulder to check if the soup is ready to be served.

Traditionally carved from wood, the wipae serves as the ancestor’s presence during the rite, a quiet reminder of lineage and continuity.

My grandpa is always the one who writes the jibang, carefully inscribing each ancestor’s name by hand.

After all the names are written, my dad is in charge of placing the jibang on the table.

The final touch-ups before the ritual begins.

The ritual begins with the opening of the door—an invitation for our ancestors to return home.

"Your nails are out of manner for the ritual,” Grandpa says.

After the ritual ends, we burn the jibang, sending our ancestors back to where they belong.

The ritual ends with the closing of the door—a quiet gesture that returns the world to the living.

The food returns to the living, a quiet exchange between the worlds of the dead and the alive.

My grandpa and dad start eating early, before anyone else can even sit down.

The view from across my grandma’s tomb.

Mom sends her wishes at my grandma’s tomb, asking her to watch over our family. The ritual wraps up here.