The Table for the Absent

On October 3rd, I flew to Korea to document jesa, the Korean ancestral rite, during Chuseok. Jesa is a Korean ancestral ritual where families honor their ancestors through offerings of food and drink. I was there for only four days, yet what I witnessed—through food, labor, and ritual—revealed more than I expected about belonging, memory, and the quiet weight of tradition.

I was born in South Korea and immigrated to the United States at thirteen, a move that fractured my sense of home. As a child, I watched my mother and grandmother prepare endless dishes before dawn at my grandparents’ house. I thought we were expecting guests, but no one ever came. When I finally asked why, my mother said, “It’s for your great-grandfather and great-grandmother.” Only then did I understand that the table was set for the dead.

After I moved abroad alone, jesa faded from my daily life, but not from my family’s. Each time I returned to Korea, I would find certain dates quietly marked on the calendar: jesa. This project follows that ritual—from grocery shopping to the final bow—through the lens of both observer and daughter, searching for what was lost and what remains.

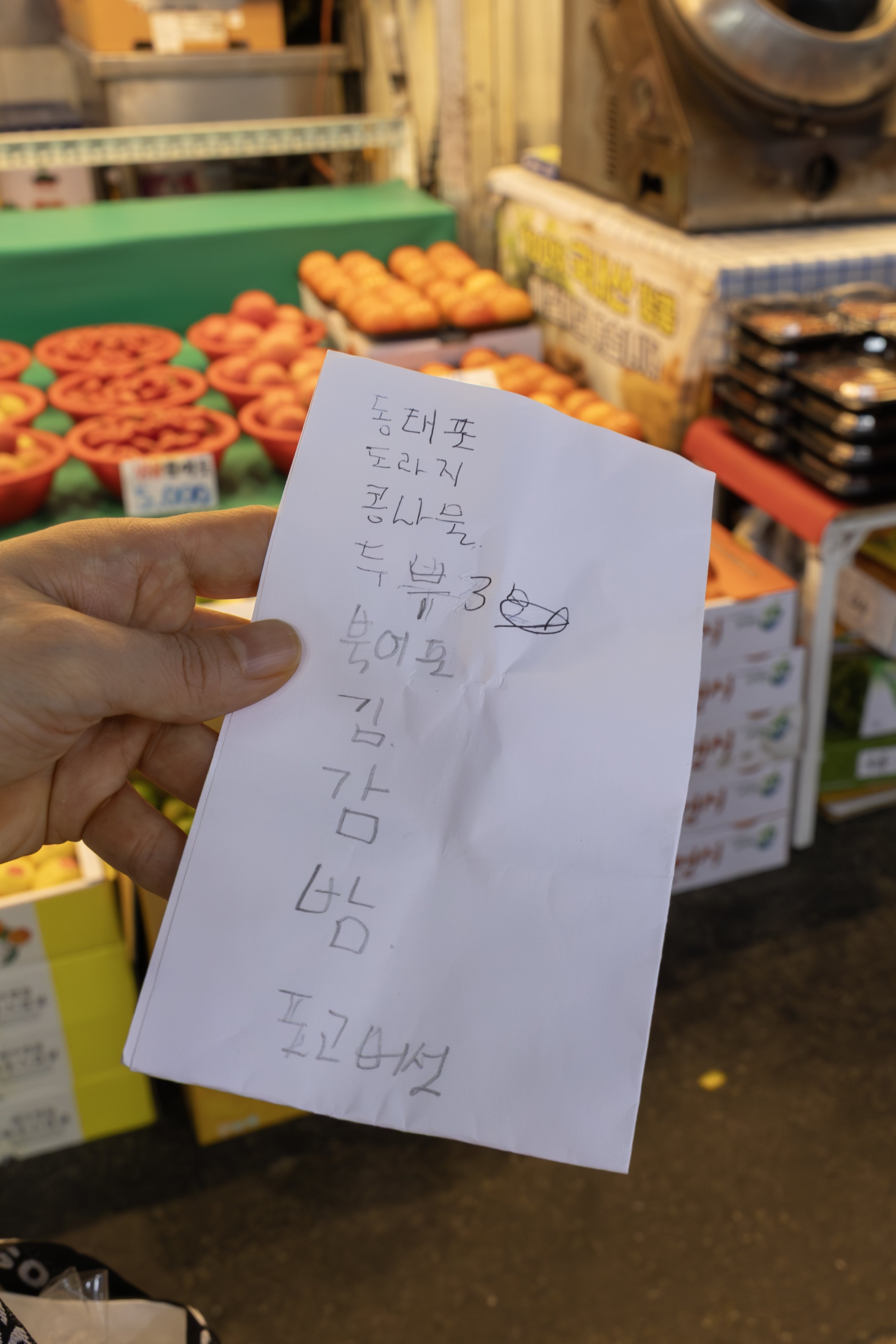

Grocery list: pollock fillet, bellflower root, soybean sprouts, tofu (3 blocks), dried pollock, seaweed, persimmon, chestnut, shiitake mushroom

Preparation day began early; I woke to the clatter of metal basins and lively conversation in the kitchen; by the time I arrived, my mom and her friend were already elbow-deep in the first round of cooking.

My mom offered me taste tests throughout the day, but she never asked me to help with the cooking itself. I was there with a different intention—as a documentarian rather than a helper—but the lack of invitation still lingered. When I finally asked why, she said, “You have bigger fish to fry.” I still don’t fully know what she meant, but I understood: I was present to observe, not to contribute. I was the taste tester, not the cook.

My mom laughed about a notorious dish made the next day: a kind of “everything soup,” where all the leftover jeon are tossed into a fish broth. In Korean, the name translates literally to “rag soup,” an unglamorous term that perfectly captures the chaotic practicality of post-ritual cooking.

My mom's favorite

Since last year, my mom has asked this friend to help her, because a nerve injury weakened her sense of smell and taste, making it nearly impossible for her to prepare the entire jesa table on her own. Her senses are slowly returning, but jesa doesn’t pause for recovery. The ritual moves on with the calendar—steadfast, immovable, indifferent to illness or fatigue. Jesa must go on, no matter what.

The day of jesa begins early. My mom woke me at six in the morning, and we left the house by seven. It takes about an hour and a half to reach my grandpa’s home—the house where my dad grew up.

All for the deads

There is an old Korean saying: “A married daughter is no longer a member of her birth family.” Rooted in Confucian patrilineal logic, daughters traditionally do not carry jesa across generations; that responsibility has always fallen to men and their descendants. Here are my aunts—my dad’s sisters—who now participate in the Park family’s jesa again, having returned after their divorces. Their presence reflects how marriage, lineage, and gender shape who is included in the ritual, and under what circumstances.

Grandpa walks in to check whether my mom and aunts are preparing the food the right way.

Grapes aren’t a traditional offering for jesa, but my grandma loved them so dearly that my aunt always sets them on the table. They sit there tucked quietly among the formal dishes—an unlisted ingredient in the choreography of the ritual.

My dad has almost never participated in jesa food preparation, partly because he was raised to believe domestic labor was not his role, and partly because of a major confl ict nearly twenty years ago. My mom and her mother-in-law once argued intensely over how jesa should be conducted and whether my mom was serving the Park family “properly.” The fallout was devastating. My mom stopped visiting her in-laws altogether and did not see them for nearly ten years. Her absence from the family home meant she was also absent from the ritual itself for almost a decade. These were years in which the ritual continued without her—years in which her labor, care, and presence were neither visible nor acknowledged. The family reconciled only after my grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, a moment that forced everyone to confront time, fragility, and what had been lost. My mom stepped back into the household cautiously at first, but once she returned, she gradually took on the full responsibility of jesa food preparation. Since then, she has become the person who carries the ritual forward, to prepare dozens of dishes on her own—quietly, diligently, and without complaint. Her role is no longer contested, but the history of that conflict lingers beneath the surface of every ritual she now leads.

To distinguish exactly whom we are serving, the names of our ancestors are inscribed on a wooden tablet.

My grandpa is always the one who writes the jibang, carefully inscribing each ancestor’s name by hand.

I can never read what he writes—the characters are all in classical Chinese.

After all the names are written, my dad is in charge of placing the jibang on the table.

The final touch-ups before the ritual begins.

Jesa officially begins the moment we open the door and invite our ancestors into my grandpa’s house. It is a small gesture, almost ordinary—just a hand on a doorknob, a brief creak of hinges—yet symbolically it feels monumental. That simple opening transforms the threshold into a passageway between worlds. Grandma, are you there?

"Your nails are out of manner for the ritual,” Grandpa says.

After the ritual ended, my dad removed the paper from the wooden tablet and took it to the garage to burn. The flames curled the edges instantly, turning names into smoke, then into nothing. This gesture marks the official closing of the ceremony—a way of signaling to the ancestors that their visit has ended, that they are free to roam back to their own realm.

The ritual ends with the closing of the door—a quiet gesture that returns the world to the living.

The food returns to the living, a quiet exchange between the worlds of the dead and the alive.

My grandpa and dad start eating early, before anyone else can even sit down.